PICTURE THIS

October 28, 2012 Leave a comment

The sketch and the doodle, the comic and the cartoon, the glyph and the graph, the grim caricature and the political ideogram. Perhaps our most convenient and universal form of expression is the line drawing. Whether you’re using a zero-gravity pen to scrawl in space, or blotting post-it notes in your office cubicle – the eternal relationship of ink on paper breeds an objective subjectivity, a rudimentary, understandable and instantly accessible portal into the 5th dimension of imagination. Here are a random selection of scribblers that mirror our skull’s interior with nothing more than 2-D tools.

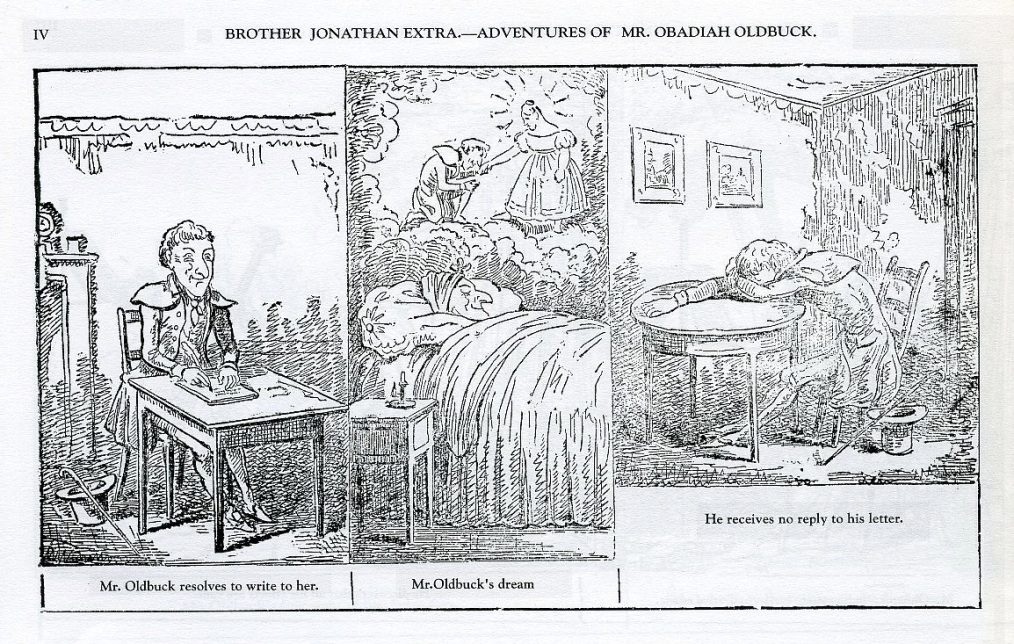

Histoire de M. Vieux Bios or The Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck by 18th century Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, is considered to be the first modern comic book. It featured a revolutionary use of interdependent words and pictures in a sequential bordered format, effectively creating time with space. Marked by its dark and weird humour (much of which still holds up today), Töpffer caricatures the madness of love to tell us the tale of Vieux Bois/Oldbuck’s repeated botched suicide attempts and frequent efforts to escape captors and rivals in order to reclaim his fiancee’s affections. The episode is an affair of mad monks, starving steeds, coffin canoes and manic chivalry. An old-school monochrome love story. A favourite line of mine is “For eight-and-forty hours he believes himself dead. He returns to life dying of hunger.”

The critics panned most of Töpffer’s caricatures as a low ambition for a greater mind, but he never designed them to be anything more than novel entertainment for children and the lower classes. In the words of iconic alternative cartoonist Robert Crumb: “Low class art of the time [was] the popular art of the times. Just in our lifetime it’s changed – Look at the comic books that came out in the forties, they were just that: crude, lurid, low-level, working class… all those artists came from working class backgrounds, all of them. Jack Kirby and all those guys. They thought of themselves as entertainers, not artistes, not like us.”

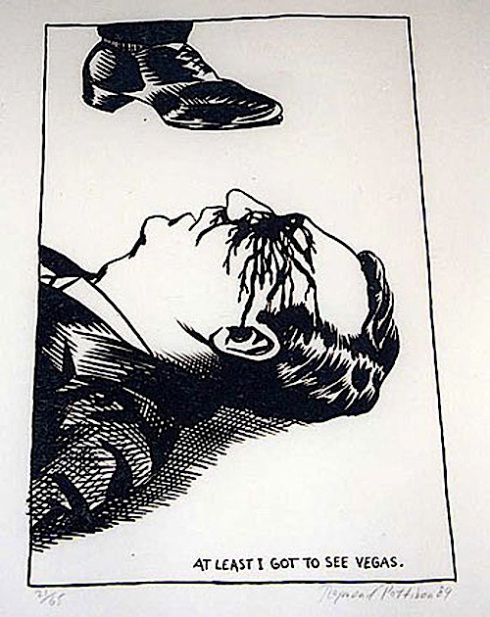

In modern society, the lines between art and entertainment are often blurred and attitudes to less revered art forms have changed over the last century, in part thanks to movements such as expressionism, minimalism and outsider art. The DIY punk movement of the 70’s in particular gave many the encouragement of self-expression through limited means.

Raymond Pettibon, known for his Black Flag and Sonic Youth album covers, carries in his ink the macabre American spirit – the world of dead presidents, mushroom clouds and domestic insanity. His graphic subjects appear rough and physical, while clear and toneless. The decontextualised comic panels are reconstructed into bombastic statements on consumerism and violence with the use of enigmatic text, resonating non-sequiturs and visceral dialogues. Pettibon’s success paved the way for many underground scribblers to transmute into recognised artists or spokespersons.

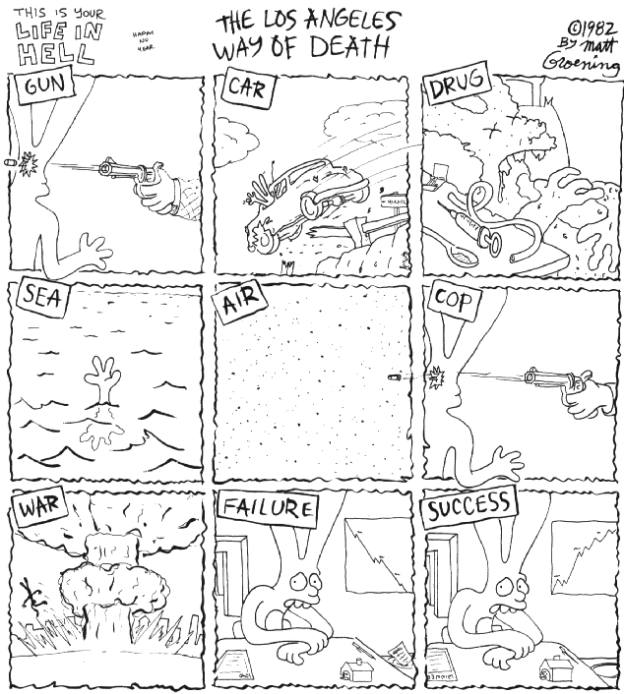

Before the satirically suburban Simpsons and phenomenally fantastical Futurama, Matt Groening wrote and illustrated Life in Hell. The strip began as a cautionary tale of 1970’s Los Angeles, taking inspiration from the drudgery of menial employment and the anxiety of urban existence. As the series developed under the alternative comics movement it became an underground success, appearing in both avant-garde magazines and weekly newspapers, leading to the animated stints which spawned the familiar family of four-fingered yellow overbites.

Life in Hell chronicled the adventures of such characters as Akbar & Jeff, “brothers, lovers… and possibly both” a symmetrical couple clad in fezzes and Charlie Brown shirts, Binky the perpetually addled rabbit self-insert and his illegitimate son, the single-eared and alienated Bongo. The latter shares his name with Matt Groening and Bill Morrison’s publishing company Bongo Comics Group which ruled beside D.C. Thomson & Co. and Marvel in my childhood education of pulp wonder.

The comic often featured pseudo-analytical charts and diagrams depicting the fractured nature of society and the human condition, this presented the simple strip as a relatable haze of geometry and anthropomorphism. It is certainly a testament to the expressive success of such rudimentary materials as the pen, paper and photocopier.

The torch of chart-comics is currently carried by cartoonists such as Grant Snider and Tom Gauld. A classic Life in Hell quote: “Love is a snowmobile racing across the tundra and then suddenly it flips over, trapping you underneath. At night, the ice weasels come.”

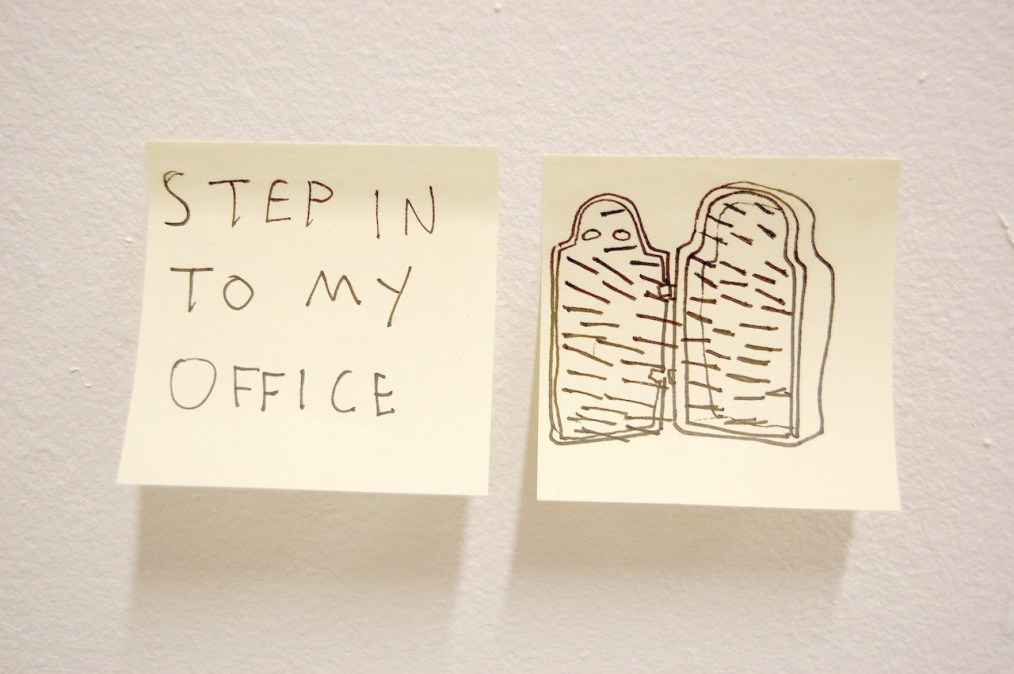

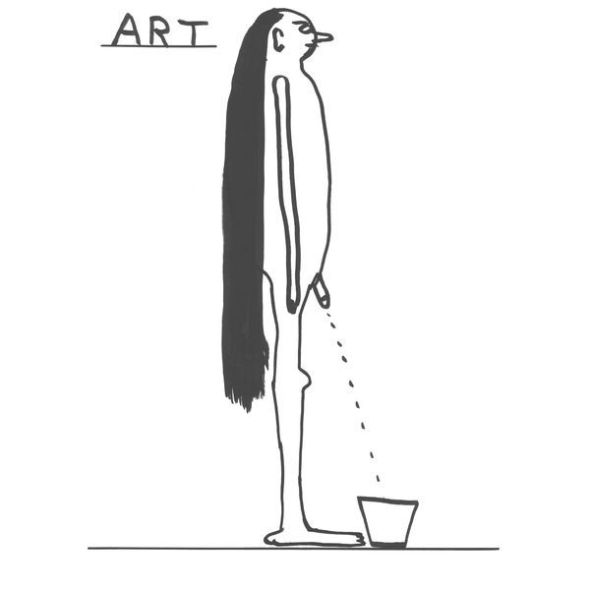

I shouldn’t be allowed to ramble on about the modern appreciation of absurd ink drawings without mentioning David Shrigley. Undoubtedly a popular and prominent figure in this movement of perceptively primitive art, Shrigley made his name through his countless publications such as Ants Have Sex In Your Beer, Kill Your Pets and Drawings Done Whilst On Phone To Idiot. In addition animation or taxidermy sculpture, the thousands of witty drawings that make up the bulk of Shrigley’s work are formed by seemingly deranged hands which challenge the mundane and the rudimentary qualifications of art. His “style” stems from a desire to abandon such a concept, it is rather “a default setting of making graphic images and text… that is avoiding any kind of craft, and therefore style”. The direct, quick and self-descriptive work reduces communication to its bare essentials and invites us into its absurd world – the sign of potency being that I needn’t waste your time describing his work at all, it speaks pretty loudly for itself.

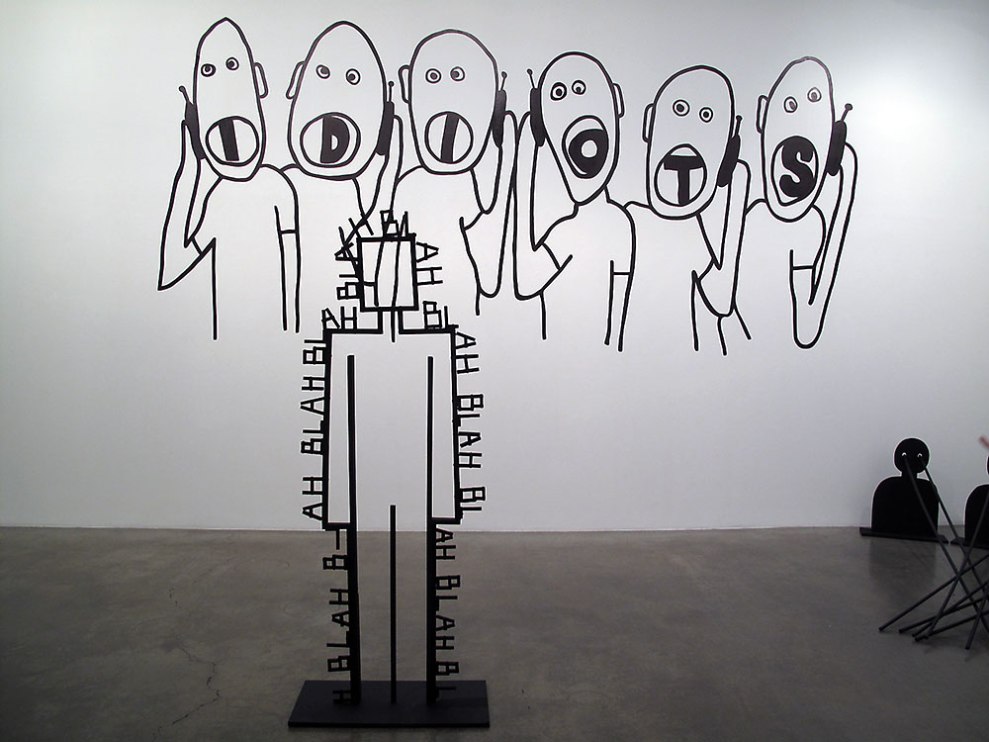

Like Shrigley, Swiss artist Olaf Breuning creates minimal things full of character, sheerly for the fun of it all. Breuning is a modest polymath, making films that blur fiction and reality, sculptures that talk to one another and even abstract paintings made of gas. He often uses the abundant materials at hand which include made-in-China plastic products, cardboard boxes and people who happen to be around. His work is a cheerful and inviting doorway into conceptual art, presenting complexity within simplicity through an unpretentious and uncomplicated philosophy of “work makes me happy”.

A potential evolutionary explanation for our art and fiction may in part be that it is an elaborate subconscious ruse to impress the opposite sex, or failing that, establish some sort of non-biological legacy. But I feel that as we homo sapiens become at our most upright and articulate, we seek to express ourselves in ways that comprehend yet exist outside of nature, as a sane reaction to an insane society, as an indulgence in or protest against nature’s complicated tangent. We imprint ourselves and our perspective of the world onto our creations, as a sort of consolidating code so that as we might occasionally feel swept away by tides of bureaucracy, genetic imperative and social nonsense, we can find each other on that democratic psychological landmass. Like the passing of notes in class or the graffiti on the wall, artistic expression, no matter how trivial, is a rebellion and a grasp at free will in a storm of clay, piano keys or celluloid film. But if those tools aren’t available – doodling in the margins of the newspaper is not a bad place to start. We create because we are greater than the sum of our atoms.

The impetus for many artists and entertainers alike is a common exercise in autonomy, a shedding of self-doubt in the name of sublime communication and conceptual exploration. Artists like Shrigley and Breuning give me faith in my own work, that people are receptive to the simpler brand of complexity. These artists in particular remind me of a quote by C.S. Lewis:

“When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty, I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”

So here are a few some more contemporary artists which embrace this freedom.

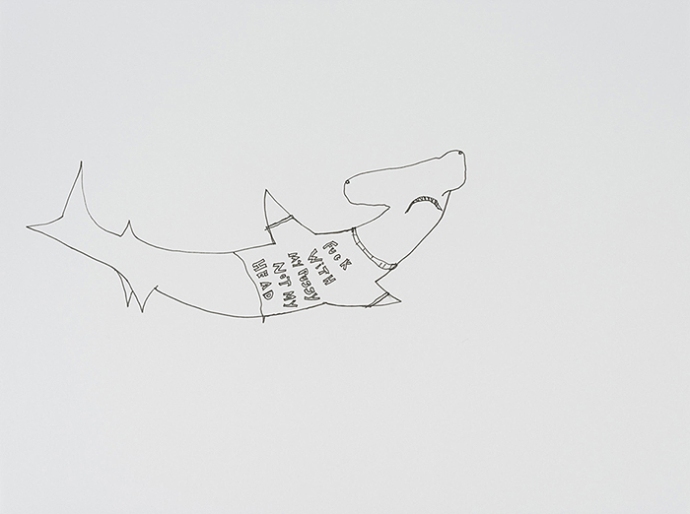

While Stanya Kahn is known for her warm and bizarre approach to filmmaking, her drawings contain a similar ethos in her telling of the tribulations of zombies, worms and deep sea fish.

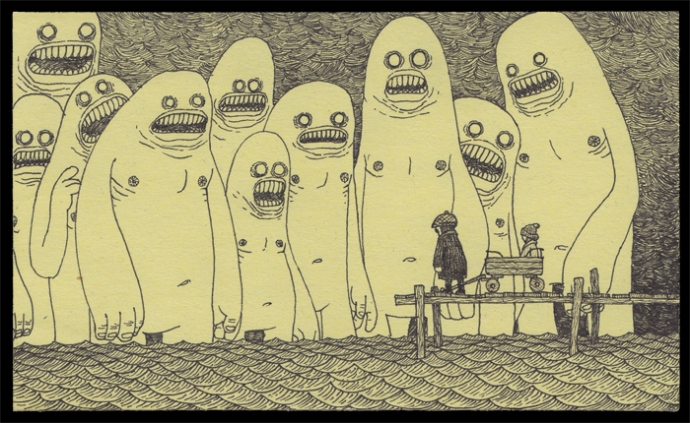

I can think of no better example of the ordinary-extraordinary juxtaposition than the drawings of Danish kid’s TV writer “Don” John Kenn. In his own words “I have not much time for anything. But when I have time I draw monster drawings on post-it notes… It is a little window into a different world, made on office supplies.” Kenn’s work is brilliant yellow bridge between the mundane and the wondrous, drawn in a pleasantly grim style reminiscent of Edward Gorey or Harry Clarke.

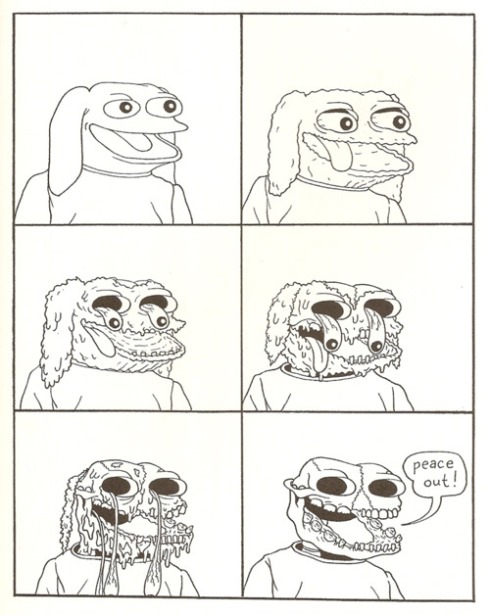

And finally, Matt Furie’s comic Boy’s Club – a hallucinatory gross-out sitcom which, like Life in Hell, features a cast of misanthropic animal-men. These anecdotal features regurgitate and parody with goofy sincerity the 90’s culture of pizza-skating and cowabungadudes.

Furie comfortably walks the line between comic book and fine artist, producing compulsive colour pencil creatures. The deadpan antics of Boy’s Club set it aside from its webcomic contemporaries which often attempt to say too much. Despite this, the comic has generated a handful of popular internet memes such as FEELS GOOD MAN and Sad Frog. In a similar vein, Andrew Hussie’s MS Paint Adventures and Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff continues this weird genre, but instead uses the internet as a medium to produce and distribute episodes of pixel-humour and glitch art. Despite not being a physical drawing, the direct crudeness, coupled with the availability of its methods, makes it and anything drawn with a mouse an intangible spiritual descendant of the graphite line.

The punk fanzine exchange and the letter sections of comic books were in many ways precursors to our modern internet, where ideas could be shared directly and composed with little more means than a do-it-yourself motivation. Today, the digital realm has become an even more convenient podium for expression wherein forums, webcomics and fanfiction are ripe with the spontaneity of the individual. Though the screen is now mightier, the pen still has its place as the inky extension of the soul. But perhaps someday, like the sword it will become retired from common use.

The tools of basic stationary are artefacts of the human mind, the keys into an abstract plain that can be drawn clear as day, a short-cut from the second dimension to the fifth. Why not celebrate this nanosecond of existence by drawing something silly?

by Theo Cleary

You can find more of these artist’s work and more on my image hoarding blog: